Hello friends,

The end of summer is upon us! Alas. In August I spent two weeks in Quebec City and Montreal, taking pictures of cathedrals and wrestling with the Québécois accent. (I did not master it.) At the end of August, I returned from Canada and promptly got COVID. This was deeply unpleasant, but I am glad to say that I appear to have dodged the bullet of post-COVID chronic fatigue, although I still have a bit of a cough.

And in September, I turned 30! Happy birthday to me!

Today: Upcoming publications, events, and a little accolade; Lisa Cron’s Story Genius.

News

I won the Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Scholarship from the Horror Writers Association.

My science fantasy story, “Cassandra Takes the Plunge,” was just published in Shoreline of Infinity’s Science Fiction and Fairy Tales Special Issue.

I’m quite fond of this story. I wrote the first draft while working in consulting after finishing my MFA; it’s the only piece of my own work that I managed to write during those months, and I was very proud of myself. The story is about mermaids, pervasive technology, climate anxiety, and the joys and horrors of self-isolation. I’d love for you to read it.

On September 28 at 7pm PDT / 10pm EDT, I’m doing a reading at Story Hour.

In October, I’m headed to Viable Paradise, a one-week workshop in Martha’s Vineyard, to study with the likes of C. L. Polk, Patrick Nielsen Hayden, Elizabeth Bear, and Scott Lynch.

On November 2, I’m teaching a one-hour workshop on how to apply the Hero’s Journey framework to short fiction.

Lisa Cron’s Story Genius

At the end of August, at the tail end of my COVID slump, I taught a one-hour workshop on using the speculative as metaphor. I talked to my students about how speculative elements (e.g. apocalypses, fairy-tale creatures, the Overlook Hotel) can be used to talk about a real-world truth or emotional state (like fear of the future, or silence, or alcoholism) in a way that’s often more resonant than coming at the truth directly.

When I asked my students why they were taking the workshop, a lot of them remarked that they were working on a novel with speculative elements, and were grappling with how to up the main character’s stakes. At the end of the class, I recommended that these students read Lisa Cron’s Story Genius.

I actually think Story Genius is deeply flawed, and I recommend it with reservation. But its central conceit, which Cron calls the “third rail,” is extremely useful and worth the price of admission all on its own:

Think of the protagonist’s internal struggle as the novel’s live wire. It’s exactly like the third rail on a subway train – the electrified rail that supplies the juice that drives the cars forward. Without it, that train, no matter how well constructed, just sits there, idling in neutral, annoying everyone, especially at rush hour...

In a novel, everything – action, plot, even the “sensory details” – must touch the story’s third rail in order to have meaning and emotional impact. Anything that doesn’t impact the protagonist’s internal struggle, regardless of how beautifully written or “objectively” dramatic it is, will stop the story cold...

What does she mean by “internal struggle”?

All protagonists stand on the threshold of the novel they’re about to be flung into with two things about to burn a hole in their pocket:

A deep-seated desire – something they’ve wanted for a very long time.

A defining misbelief that stands in the way of achieving that desire. This is where the fear that’s holding them back comes from.

Taken together, these two warring elements will become your novel’s third rail, the live wire that everything that happens must touch, creating the emotional jolt that forces your protagonist to struggle as he tries to figure out what to do. This is what lets us know what matters most to him; it’s the emotional yardstick by which readers will measure the meaning of every event, every plot twist, every turn.

It’s easy to think that a story is a chain reaction of events, one after the other, but as Cron points out, that’s merely a plot. (Or, at worst, not even that!) The engine that is a character’s internal struggle – what they want, and how they’re stopping themself from getting it – is what turns the thing into a story. That internal struggle needs to be tethered to the story’s events, just as a subway car is tethered to a live wire, every single step of the way. (Of course, you do still also need the subway car.)

This dogmatic statement that everything in the narrative has to touch the protagonist’s internal struggle, or else those parts of the narrative won’t run and will just sit there stagnant, was a game-changer for me. I read Story Genius right before drafting the manuscript that got me into Pitch Wars, and in my opinion it changed the manuscript completely, made it into, as one reader said, something that “takes the basic plot of a schlocky creature feature and injects it with real human pathos.” One of the tricky things, actually, about describing my manuscript to people, is that at first glance it looks like it’s about big cats and Antarctica and mortal combat, but really it’s about self-forgiveness and childhood trauma.

Which is thanks to Story Genius! Otherwise, I might have written merely a glorified monster movie. No shade to monster movies, of course, I love them a lot. I’m especially partial to The Alligator People.

So, questions to ask yourself:

What does my character want, really want? (Note: This might not be what she thinks she wants.)

What internal misbelief or quality of her character – as opposed to an external obstacle – is stopping her from getting it?

And, a valuable follow-up question: How did she get this way? What happened in her past to make her like this?

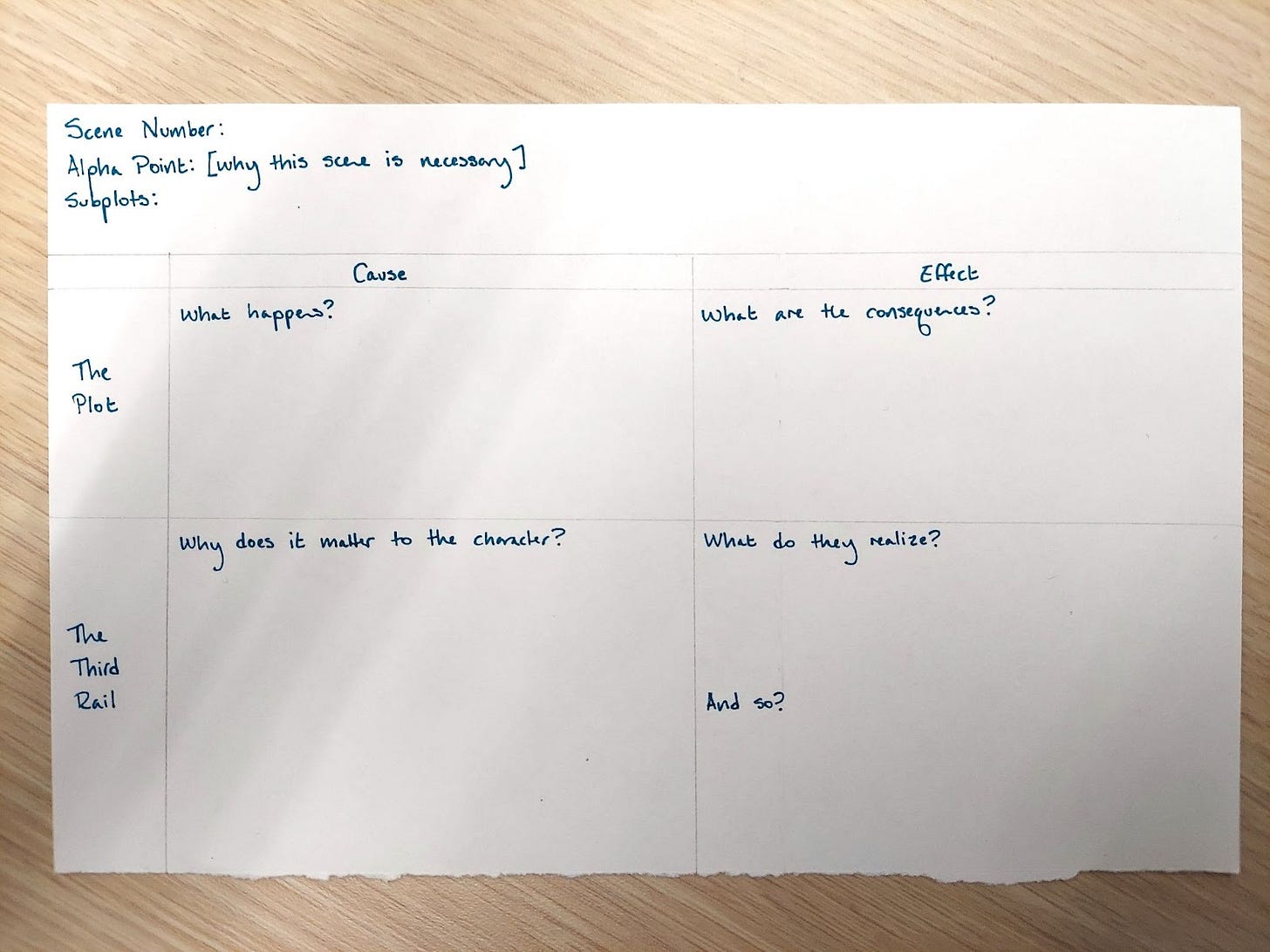

I’ll be honest, though: The rest of Story Genius doesn’t do it for me. For one thing, it’s pretty repetitive; if you cut out all the repetition, I think you’d have something akin to a Medium article. The “case study” used throughout the book is a novel-in-progress by one of Cron’s colleagues... which was never completed, let alone published. Cron also talks a lot about how people respond to certain storytelling patterns because of “brain science,” in a way that I find needlessly Western-centric and also frankly unrigorous. And she suggests a lot of prescriptive exercises for how to do the work, such as writing a “Scene Card” for every scene in your unwritten manuscript. A Scene Card is a visual tool for tying the character’s internal arc to the novel’s external events, and it looks like this:

Personally I would rather take up professional volleyball than do this. Yes, I want to write books, but I also want to experience joy.

The third rail, though. That’s worth writing home about, and worth picking up the book from the library if you can get it. (And pro tip: Don’t buy the Ten Speed Press first edition! Pages 57-88 are missing. Ask me how I know.)