On "Save the Cat! Writes a Novel"

I read this book on plotting so you don't have to.

Hello friends,

Happy New Year! I hope your 2023 is off to a pleasant start. I’ve just returned from Lancaster, PA, where I neglected to take any pictures at all but DID pick up a couple of silly souvenirs:

Today, I want to talk about Jessica Brody’s Save the Cat! Writes a Novel. There’s a good chance you’ve already heard of this one! I often see it referenced by folks talking about how they got their agent or their book deal or what have you, and Isabel Cañas even mentions it in her post “How to Write the Thing Fast, Part I,” which I wrote about in November. So it comes highly recommended.

Which is fascinating to me, because I frankly did not care for it. Read on!

News

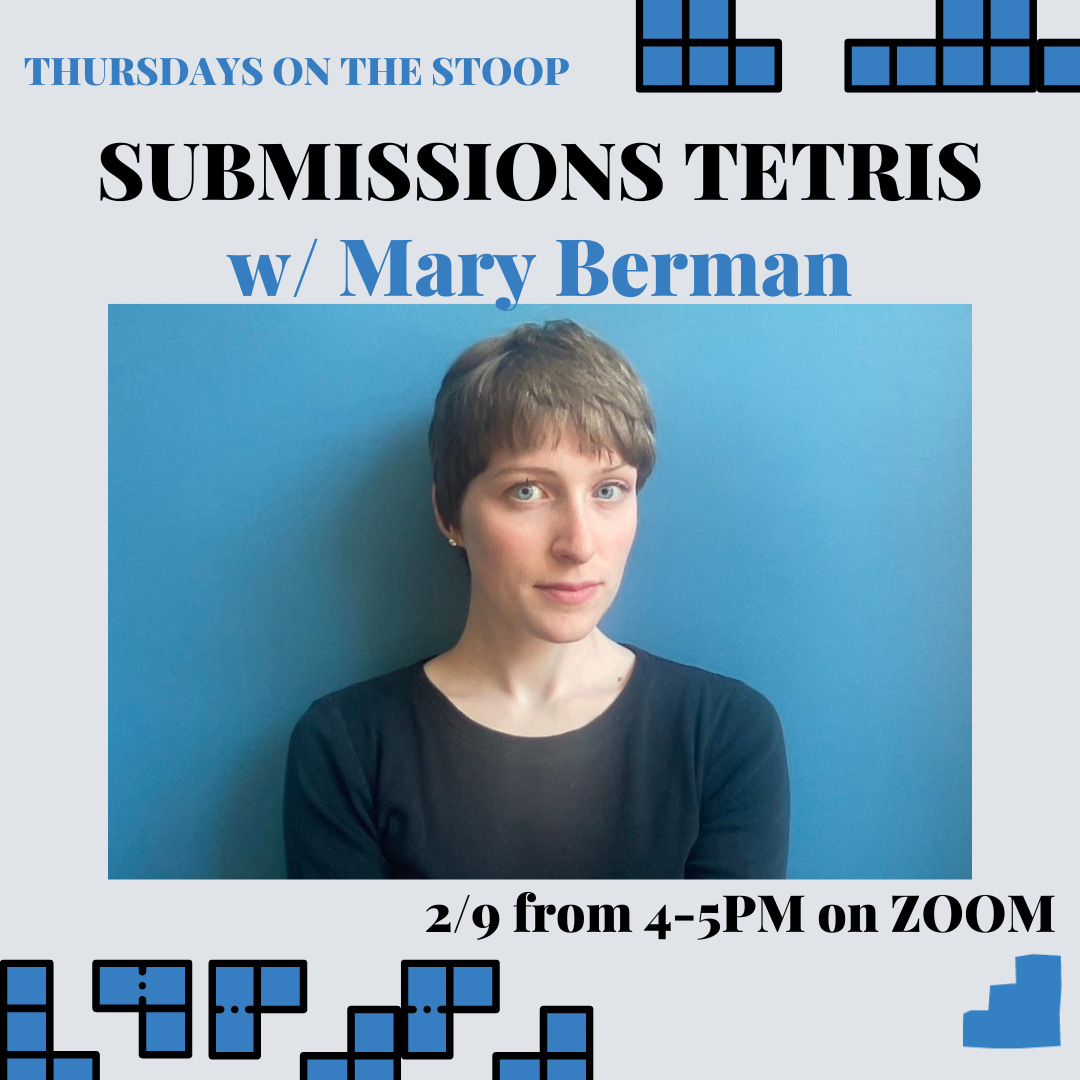

On February 9, 2023, I’m teaching a one-hour workshop on submissions tetris.

In March 2023 or thereabouts, I will guest the Horror Writers Association newsletter’s dark poetry column.

My horror-leaning Shakespearean sonnet, “Ophelia After Her Distress,” will be published in Shakespeare Unleashed in April 2023.

My essay “Nostalgia, But Make It Stressful: Fantasy Game As Pressure Valve” will be published in the British Fantasy Society Journal’s Special Issue on Fantasy and Gaming in 2023.

My essay “‘You Have to Cook It In Your Own House’: One Family’s Pork and Sauerkraut Ritual” will be published in Heritage Local in 2023.

Jessica Brody’s Save the Cat! Writes a Novel

Save the Cat! Writes a Novel is a how-to guide on how to design a book-length plot. In its own words:

The first novel-writing guide from the best-selling Save the Cat! story-structure series, which reveals the 15 essential plot points needed to make any novel a success.

I have one (1) nice thing to say about it, which is: I actually love the Save the Cat beat sheet. (A beat sheet is a broad-strokes map of a narrative’s key steps, or “beats.”) I used it in my Pitch Wars novel, and I intend to use it forevermore.

But I’m afraid to say that the book that describes the beat sheet simply does not do it for me. There are three times as many examples as there are actual points. The number of examples is seconded only by the number of writing exercises, which are not my jam. And the prose style feels like it’s targeted at a child.

(Caveat that I think the book might have felt fresher and more edifying if I’d read it a decade ago, and if you’re at the start of your novel-writing journey, you might like it more than I did.)

The good news is, I read this book so you don’t have to, and I’m going to tell you the most important takeaways. The biggest one? Skip this book and go straight to the beat sheet. Brody’s put it on her own website for free.

Otherwise, here are her four main points:

The protagonist

According to Brody – and some other folks, too – your protagonist should have three elements:

A problem: A key character flaw

A want: A goal they’re actively pursuing

A need: Something that they actually need to fix about themselves, which is usually not the same as what they think they want

What your character does to try to get what they want becomes the “A Story,” or the actual events of the novel. What happens to your character so that they solve their need and actually change as a person is the “B Story.” Your job is to knit the two together.

If you read my newsletter on Story Genius, you’ll notice some similarities.

The beat sheet

Brody outlines fifteen “beats” that your narrative should hit and when. Again, you can go straight to her website for these.

And like I said, I do think they’re pretty good! A lot of folks hate a beat sheet, especially one as rigid as this, but what can I say? I like rules. And I find, personally, that there’s a lot of flexibility and wiggle room between the beats.

Genres

Brody lists ten genres into which she claims all narratives can be grouped – even though, as she adds, “Novels are complex. They don’t always fit neatly into just one category” – but most of them are variations on the standard Hero’s Journey, and all of them map to the aforementioned beats. So, again, you can skip straight to the beat sheet, imo.

Pitching

Finally, Brody shows you how to use the material from your, you got it, BEAT SHEET to craft a logline, which is basically an elevator pitch; and a synopsis, which is a one-page summary of your book.

For the synopsis, you can basically line all the points from your beat sheet up next to each other and massage the prose, and you’ll end up with a one-page summary of the book, which is indeed handy.

I’m going to diverge from Save the Cat for a moment to tell you that I actually find the logline framework in Query Shark more helpful. (Query Shark is a literary agent’s guide to writing query letters. No joke, it changed my life.) Here’s what to include in your logline:

Who is your protagonist?

What do they want?

What happens if they don’t get it? In other words: What are the stakes?

So, for instance:

[1] My protagonist is Nina, a felinologist in Antarctica.

[2] She wants to keep her cat safe from the big-game hunter who wants to kill him. (After all, who among us would not die for their cat?)

[3] But what she needs, although she would bite the head off anyone who dared suggest it, is to learn to let other people into her life. And…

[4] The stakes: If Nina doesn’t grapple with her past and why she’s like this, she’s going to get herself and her cat both killed, and her baby niece, too. So:

For nine years Nina has lived in Antarctica, caring for a freshly thawed, thirty-foot sabertooth cat, the only creature she’s ever truly loved. [1] But when a billionaire big-game hunter arrives [2]—just days after Nina’s estranged sister dies, thrusting a child into Nina’s care [3]—Nina finds herself trapped in mortal combat: fighting for her cat, her niece, and her life, and battling not just her enemy, but her own past. [4] Godzilla vs. Kong meets the interiority of Severance.

There you go! Fifteen essential plot points needed to make ANY NOVEL a success!

😒

What about you? Are you the sort of writer who thrives on a beat sheet, or do you prefer to wing it? Write me back and let’s discuss!

I do not care for things like beat or character sheets, simply because I've written enough books to understand how the pacing works--also, pacing varies according to the sort of story you're writing.

But part of it is my resistance to worksheets in any form. I'm a former middle school teacher, and while worksheets have their place, they can become formulaic and overused. I prefer to go by the rule of thirds--in other words, by the first third, I need to have laid out the initial conflicts, the second third is the intensified conflicts, including assorted twists in the story, and the final third is the climax/resolution of conflicts.

Since I've figured this aspect out, I've had a lot fewer issues with that infamous "muddle in the middle." I tend to create chapter synopses as I write, unless I'm writing something like four POVs. Then I might use a scene matrix, just so I can balance POVs and know where everyone is and why they're doing what they are in each scene. That was absolutely crucial when I had characters spread out fighting a war on multiple fronts in a fantasy world. Or when I had a fast-paced, multiple-viewpoint story with characters dealing with The Big Issue both on Earth and on the Moon/in space.

I find that most character sheets tend to focus on the superficial stuff. If I need to figure something out about a character's motivation or backstory, I'll often write a short story about it. That has the additional feature of providing an entry point into that world for readers. Most of my series have a number of worldbuilding short stories that tell the backstory of the world and its main characters. Sometimes I incorporate elements of the short story into my books, most notably the "First Meeting" short story in my Martiniere Legacy story. It ends up being rewritten from a different point of view in BROKEN ANGEL: THE LOST YEARS OF GABRIEL MARTINIERE.